A discovery in Provence

Although my origins aren't particularly important in terms of my active participation in this project, they are more important for this article.

I was born in Avignon, a town close to where I grew up, but also in Gordes, where I spent my school holidays, so I'm what you might call 'Provençal', and more broadly 'Mediterranean'.

When you say the word 'Provence', you imagine fields of lavender, cicadas, summer heat... and Provençal fabrics. And it's on this point that I want to come back to you, because this summer holiday with my family made me discover something I'd never imagined...

Photograph BOUYSSE Jean, personnal collection

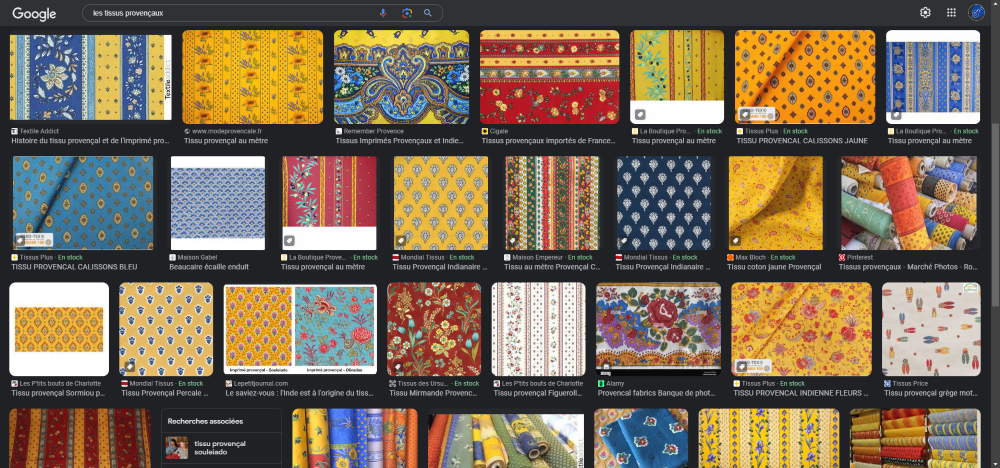

Provençal fabrics

Here's what you can find by typing "Provençal fabrics" into a search engine

In general, the characteristics are :

- shimmering fabrics

- bright colours

- multicoloured fabrics

- nature-related motifs

- small, repeated motifs printed fairly close together OR/AND complex arabesques

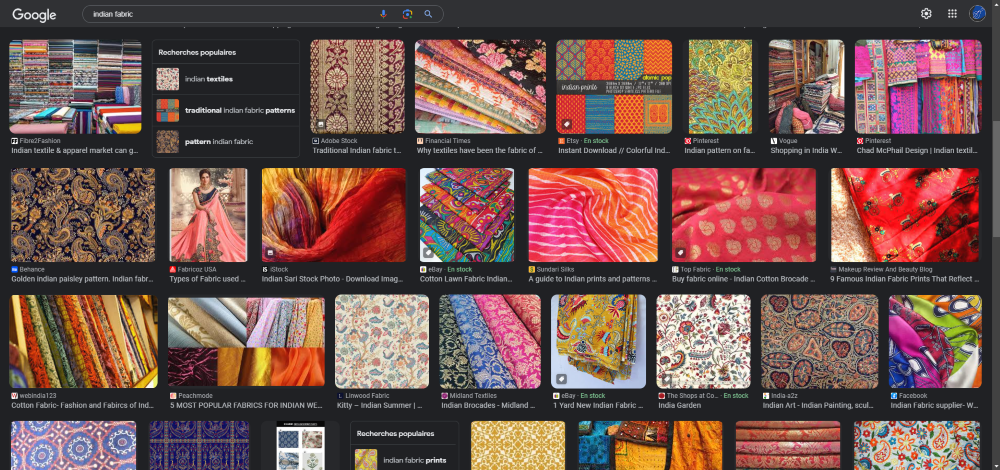

This description of Provençal fabrics corresponds fairly well to what we see for Indian fabrics.

Let's repeat the same principle: "Indian fabric" in a search engine" and the results are similar.

The choice of background colours is, however, slightly different, less...yellow

So is there a correlation? That's the aim of this article

A bit of history

Two women spinning white thread (between 1780-1858) Credit The New York Public Library

Nowadays, cotton is not really considered a "noble material", but this has not always been the case.

In fact, did you know that Asia is the continent where cotton cultivation began? The Indus Valley civilisation is thought to have started growing cotton in 3000 BC. Research in the surrounding area dates the cultivation and use of this plant back to 5000 BC...!

While the history of the expansion of this fibre is interesting, I'd like to focus on its arrival in Europe in the form of "Indian cotton", between the 16th and 17th centuries.

In Europe, textiles are produced from flax, hemp, wool and silk.

No cotton in sight... Cotton is a tropical plant that requires a lot of water. This is why it is not found in Europe, where the climate is temperate.

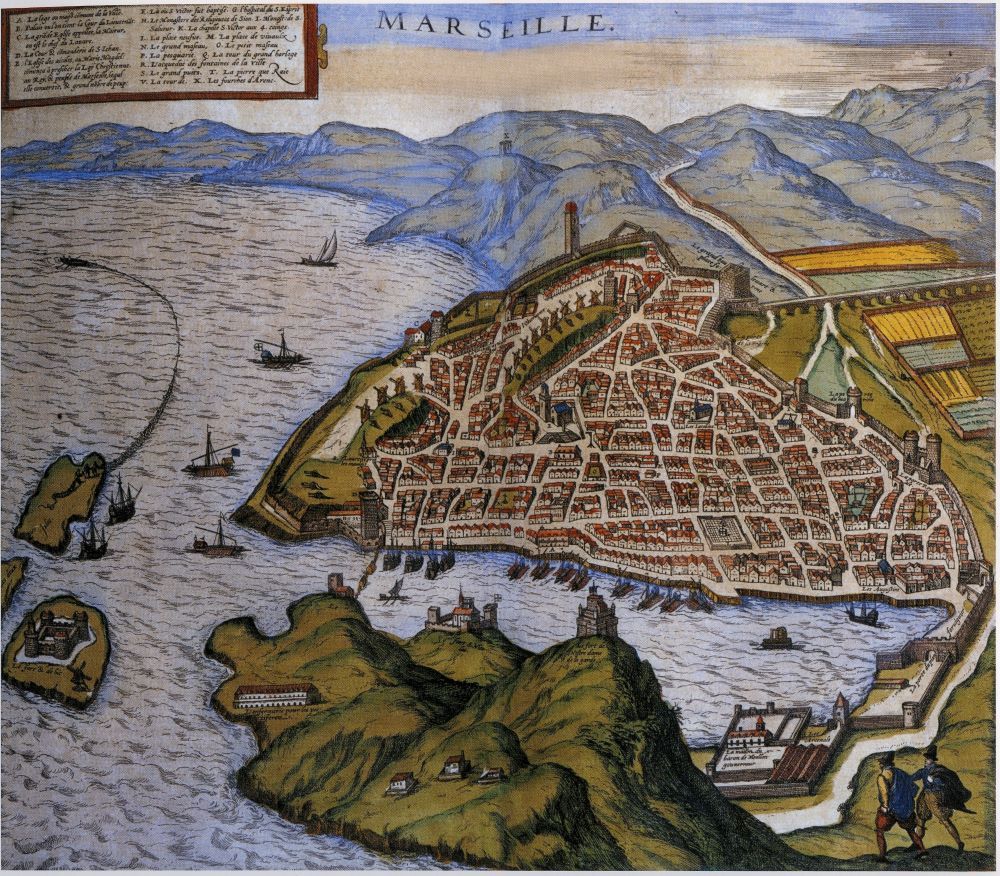

Cotton therefore arrives mainly via the port of Marseille.

Why Marseille?

Since the 16th century, Marseille has been one of Europe's leading ports for importing cotton fabrics from India, Persia and above all the Ottoman Empire.

What's more, the Comptroller General of Finances, Jean-Baptiste COLBERT

- in 1664 created the Compagnie Françaises des Indes Occidentales, increasing imports to Marseille tenfold

- in 1669 freed the port of Marseille from all customs duties, with the exception of goods destined for the interior of the country and colonial products. This gave a privilege to the city of Marseille, as well as to the neighbouring regions, which developed their trade.

Marseilles also exported to neighbouring countries as a well-established intermediary in the trade of exotic products.

Map of Marseille (1584), engraving taken from the Atlas by Braun and Hogenberg : Civitates Orbis Terrarum. Source Wikipedia

For further information on this subject (in French):

Indian Ornament no. 4: Ornaments from woven fabrics and paintings on vases exhibited in the Indian Collection, now at Marlborough House, 1856

Source The New York Public Library

Oriental dyed and printed cotton became increasingly popular in the 17th century.

Its success was due to :

- the beauty of the designs,

- the shimmering colours

- the fact that the fabric retains its bright colours and patterns despite being washed,

- its rarity (only imported)

- and its lightness

These fabrics spread rapidly throughout the kingdom, notably via the Beaucaire Fair.

It's been such a success that...

Indian cottons even appear in literature, as an important fashion element.

For example, Molière refers to them in "Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme" (1st published in 1670).

Here is the line in question, from the Bourgeois Genthilhomme to his dancing master:

-I had this Indian made for me [...] My tailor told me that people of quality were like this in the morning.

The image opposite shows a fine garment in Indian cotton, complementing this man's typical attire of the time.

"Follow me so that I can show my clothes around town".

Engraving of Molière's "Bourgeois Gentilhomme". Credit Wikipedia

The nobility and the bourgeoisie took hold of this fabric, but so did the lower classes.

Print on calico, artist unknown, 1805. Source The New York Public Library

In fact, in response to this success, "indienneneries" sprang up in the south of France, with "indienneurs" imitating Indian cottons, by printing colourful motifs on calico, using wood-carved stamps, etc.

Souleiado, the famous manufacturer of Provençal cottons, explains on its website that the 1st "indienneurs" workshop in Marseille opened in 1648, with a master carter and a wood engraver determined to combine their skills to reproduce these stamps.

This garment stamp shown opposite is a 3D scan carried out by our NPO Objet Témoin. See how the colour is still impregnated into the wood, and note the precision of the carving.

The object may appear rudimentary, but it was no easy task for the Europeans to reproduce it and achieve the same finesse in the motifs.

It was above all the dyes used that caused the Indians the most problems, as the ones they produced were of much poorer quality and quickly faded with washing. Indian artisans had long mastered this craft and kept their secrets well!

Thanks to the arrival in Marseille of colonies of Armenian merchants and technicians with useful know-how for our Indian weavers from 1672, and with the support of COLBERT, Marseille became renowned for its quality cotton fabrics. This was fortunate, as demand was growing exponentially, and it was becoming increasingly difficult to meet it.

A sudden stop

Faced with this growing success, Indian cotton fabrics were a major competitor for the more traditional French textile industries. The latter protested and asked the Kingdom of France for protectionist measures that could be described as drastic.

Louis XIV prohibited the manufacture, marketing and wearing of Indian cotton fabrics on 26 October 1686 with the Treaty of Louvois.

Decrees ordered the destruction of the engraved wooden stamps needed for printing on fabric, sometimes in public places. The penalties were serious: wearing these garments could be punished by the galleys, and selling them could lead to hanging...

"This little war, which was more bitter than that of the demi-castors, lasted seventy years and was illustrated by heroic feats on both sides. It was the intendant Barillon, in Pau, who, finding a bourgeois woman in the street with an old painted canvas apron, tore it off her and went to burn it on the spot at the forge of a merachal. It was the Marquise de Nesle who, having just had four pieces of Indian seized and cut to pieces by the aides, reappeared a few days later at the Tuileries wearing a dressing gown of the same fabric.

Between 1686 and 1716, more than thirty rulings attempted to bring Parisian women to their senses. The gate clerks at the gates of Paris made women undress. Eight or nine hundred seized dresses were burnt in the streets in a single day. A decree in July 1717 imposed the penalty of the galleys on anyone found to have brought in prohibited fabrics or to have given shelter to a fraudster. But the severity of the penalty only served to increase the popularity [...]"

source : site Rituel et matériel

This prohibition (which came about shortly after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685) forced many craftsmen into exile or underground, as many of them were Protestants. They headed for more "lenient" cities, such as Avignon, still under papal authority (until 1791), Switzerland and Italy.

Smuggling also became very important: Aix-en-Provence became its capital.

The proximity of the two towns meant that the cotton, smuggled in from Marseille (some of which was imported by the Compagnie Françaises des Indes Occidentales, founded by COLBERT in 1664...), was stored in the town's noble houses, and was therefore untouchable by the authorities.

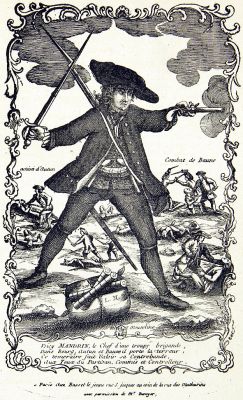

Engraving of Louis MANDRIN, notorious smuggler of tobacco, clocks and... Indian cotton fabrics (1725-17555) Source Wikipedia

Dressing gowns

Indian cottons, still prohibited, became a coquetry of the private sphere of the well-to-do and gained in popularity.

This oil painting depicts a man in his private life, wearing a dressing gown, which was called "Indian" after the fabric used.

Linings

The linings (supposedly the invisible part of the garment) were adorned with shimmering colours and patterns, defying the ban without really revealing them.

This example of a "droulet" from the Museon Arlaten, whose lining is made entirely of Indian cotton, clearly shows the desire to continue wearing these fabrics.

What is a "droulet"? Well, the Ministry of Culture can tell you more about this cultural asset on this page :)

Upholstery

This lucrative trade continues: Indian cotton fabrics are also used for interior decoration, such as the famous Piqué de Marseille, a fine example of which can be seen opposite.

What is "piqué de Marseille"? It's two layers of fabric between which cotton wadding is inserted, and held together in pretty patterns by embroidery. It is used to make bed throws, cushions, baby blankets, etc. Of course, the visible fabrics used are our famous Indian cotton fabrics.

Marseille didn't create this technique, because the Indians had already been using it for a long time: the Kantha technique. In English, there's an equivalent: they call it quilting.

Not to be confused with 'boutis', which uses an equivalent technique, but uses white cotton and must allow light to pass through, as shown in the installation in the photo opposite, taken at the Musée du Costume Comtadin in Pernes-les-Fontaines.

This superb museum displays examples of magnificent boutis, as well as costumes (authentic or reconstructed) of typical Comtat garments. And I can assure you that Indian cotton fabrics are almost always present!

Boutis is also listed in the national inventory of intangible cultural heritage under reference 2019_67717_INV_PCI_FRANCE_00434.

Abandoning babies

Yes, you read that right....

During my visit to the Souleiado museum, I discovered a rather surprising aspect of the use of Indian cotton fabrics: from the 12th to the 19th century, there was a system for abandoning babies or newborns at the Hôtel Dieu in Marseille (a system also used elsewhere, but I'll concentrate on Marseille).

The system in question involved placing the baby in a wooden cylinder that pivoted on its axis, allowing people inside the building to retrieve the child from outside, while leaving the person who had placed it anonymous.

Many babies were abandoned, and unfortunately there was no shortage of reasons for this. Fortunately, mothers sometimes returned to collect their child after a few years. But how could they recognise their parentage if they had concealed their identity?

Well, the mothers would leave with the baby either a special garment or a piece of Indian cotton. In the case of Indian cotton, the baby had one half, and the mother kept the other half. Babies were then named according to the cloth or garment left by the mother. When the mother wanted her child back, she had to show her half of the cloth.

1759: the end of Prohibition. A 73-year game of hide-and-seek

So what?

Madame de Pompadour at her embroidery frame by François-Hubert Drouais (1763-1764). Credit National Gallery of Londres.

Painted AFTER the abolition of Prohibition (1759)

I can't resist sharing this sublime painting of Madame de Pompadour as an Indian woman

And so, as someone from the Provence region who grew up with clothes sewn from so-called 'Provençal' fabrics, with a grandmother who sometimes made boutis, and surrounded by images of Arlésiennes or the costume of the Comtat Venaissin (the former name of the Avignon region), I was very surprised to learn that this textile heritage didn't really belong to us.

It came from India and the Levant, imported by boat via Marseille, and had long been part of the cultural heritage of these regions.

Of course, I haven't gone into the full, complex history of this stormy episode, so I'll leave it to people who are far more professional than I am.

Interesting places visited for informations

Located in Pernes-les-Fontaines, this conservatory and museum continue to perpetuate the tradition, with free access to exhibitions and sewing workshops throughout the year.

The museum is housed in a magnificent former fabric shop, and will instantly transport you to another era.

If you're ever in Arles, don't hesitate to visit this superb museum, which offers an insight into the culture and people of the region. Initiated by Frédéric Mistral, the museum continues today with the original exhibitions, as well as new ones that go even further in the quest for regional identity.

Continue strolling through the streets of Arles, your eyes filled with the magnificent patterns of Indian cotton, and meet Sabine from Delhi Ka who will certainly have what you're looking for to dress you the Indian way, but be careful! Quality! I had to force myself not to buy the whole stock of fabrics because I know that even if we do reconstructions of Indian servants, it's doubtful that most of them wore such beautiful fabrics.

When you're in Tarascon, stop off at the Musée Souleiado. Housed in the Aiminy town house, it will take you back in time to the making of Indian cotton, giving you access to the rooms that were once used for this purpose. Immersion guaranteed!

You might be tempted to buy Provençal-style furnishings, and you'll find them in this shop, which has been running since 1818 in Saint Etienne du Grès, with a new collection every year.

The road where they are located is also called "le chemin des Indienneurs", a tribute to history!

The pride of these regions comes from elsewhere. The exoticism brought by this elsewhere has provoked such a craze that they have defied the prohibitions and appropriated the codes, to the point of becoming their own.

Working on the Forget me not project allows me to explore the links between cultures and the importance that history has on our lives today. And while this article is just a drop in the bucket of our cultural heritage, I'm pleased to have been able to explore that drop and set out a few aspects of it here.

And where are you? What story could be lurking there? You might be surprised :)

Don't hesitate to share on our social networks anything surprising you've discovered about the history of your city/region/country that also comes from elsewhere.