Cultural synthesis among the indian indentured labour of the 19th century

Imagine you are on Reunion Island in the 19th century. How would you identify a person’s background from a distance? From his/her dress, of course! Dress is among the more visible expressions of culture; language is its essence. Indian indentured labour in 19th century European colonies developed a composite culture that combined elements from various regions, religions, and castes of India. Adherence to culture prevented them from being westernized, and evolved them into a distinct class.

Culture & Class: Expressions of Common Interest

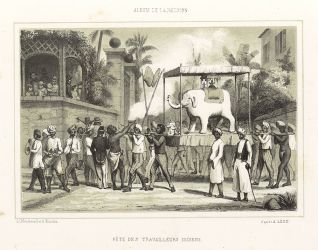

Long processions are the hallmark of Muharram, an annual Islamic festival. In 19th century Trinidad, it became the multireligious Hosay Carnival among Indian indentured labourers. Participants must have worn similar dresses, for the celebration was also a show of unity. No wonder, colonial authorities brutally targeted its 1884 edition!

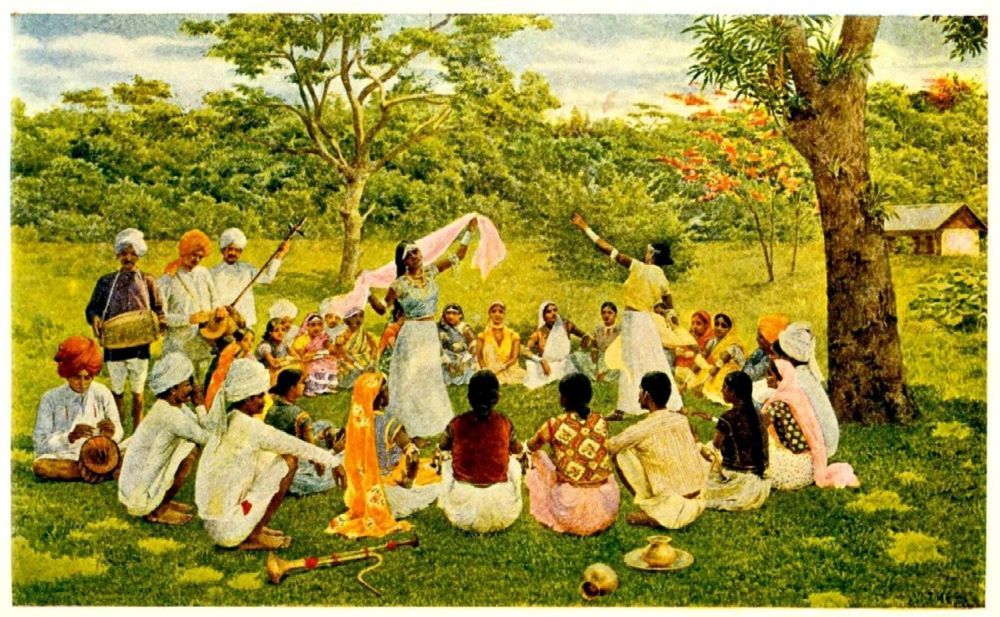

Religious Celebration by Indian Indentured Labourers on Reunion Island.

With the courtesy of IHOI (Iconothèque Historique de l’Océan Indien)

With circumstances blurring the lines of religion and caste among Indian migrants in the then European colonies, a composite culture emerged and inspired them to endure poverty, colonial onslaught, and native animosity.

A Zillion Dollar Question: What is Culture?

Culture is the sum total of lifestyle, all ways of life of a certain people. A broad term, it encompasses language, dress, cuisine, religion, arts, music and the like. Culture is also a rather abstract entity for it includes the social norms, traditions, belief systems, as well as the code of morals, manners, and laws of a particular people. Why abstract? Because the elements of culture keep evolving while also competing with those of others. And because even its creators cannot agree on what it really is! You have to feel it.

Class formation occurs when experience, values, and traditions generate similar socio-political interests for a group of individuals. With broadly alike traditions, Indian workers had similar experiences when traveling, working on plantations, striking against planters, and facing the wrath of the natives and planters.

Language, dress, and festivals were the three ways Indians in Trinidad utilized to maintain culture. Such identity management prevented their westernization, which most African slaves of the earlier time had no alternative but to comply with. It also isolated them from the white-black class conflict, but invited hostility from the island’s Africans and white middle classes.

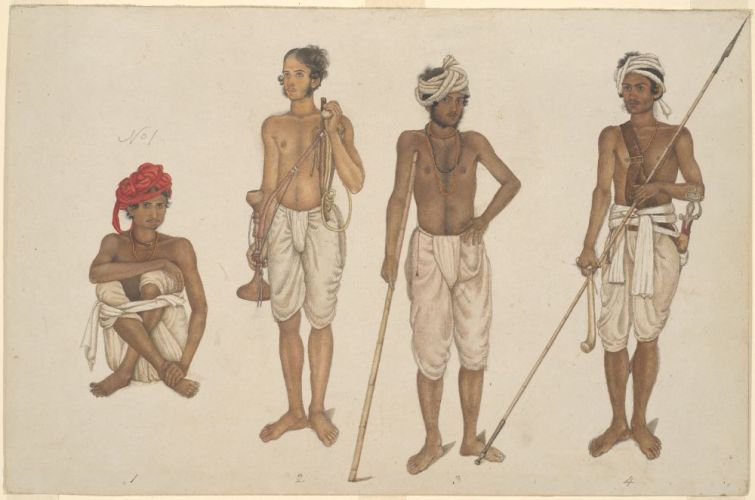

Freshly arrived Indian Indentured Labour in Trinidad. Credits: Wikipedia

Perhaps, these rivalries stemmed from the wealth that Indian workers accumulated over time. As in Trinidad, so in Mauritius; the permission to own land proved the gamechanger, catapulting them into the middle classes. Land ownership also made them settle permanently.

With local variations, similar cultural developments must have occurred for Indian indentured labourers in other 19th century European colonies.

Dress: The Visible Expression of Culture

Contemporary photographs, portraits, art, and descriptions are an excellent source to understand clothing of a particular era.

Take the Mai-Baap (mother-father) memorial in Kolkata (Calcutta) and its identical twin at Paramaribo, Suriname’s capital.

Dhoti or lungi

Dhoti or lungi covered men’s lower bodies.

The optional, loose fitting kurta (tunic) for upper body extended below knees.

Pheta (turban) protected their heads from the punishing sun. Many simply wrapped their head with a cloth that served as a sun shield and makeshift towel. Turbans in India also indicated social status.

Dhoti is an unstitched rectangular, 15 feet (4.5 m) long garment. Wrapped around the waist, one of its ends goes between the legs and is tucked inside the waistband, on the back or front. It resembles knee length, baggy trousers. Some dhotis extend below the knees. Cotton dhotis and kurtas are for daily use, silk ones for special occasions.

Other examples of dhoti

The many names & variants of Dhoti

Lungi is common in the hot, humid parts of India, south and north. It is also a rectangular, unstitched garment wrapped around the waist, but its one end is not pulled between legs. Best described as an ankle-length men’s skirt, it looks like the sarong.

The Bidesiya Project: Remembering the Dear Departed

Folk songs in Bhojpuri, the vernacular language in Bihar, depict a whole range of emotions, particularly sorrow, of those leaving for distant lands and of the family they leave behind. Bidesia Project by Simit Bhagat is compiling these songs. “In Search of Bidesiya” is his documentary that premiered at 18th Dhaka International Film Festival in 2020. Bidesiya is a kind of song in eastern India, the topic being a woman remembering her foreign-based husband. There is also a 1963 film by the same name.

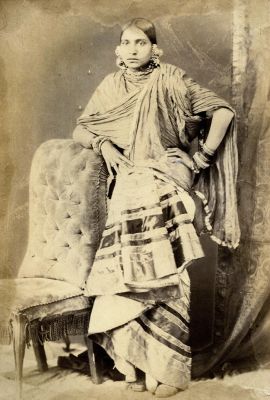

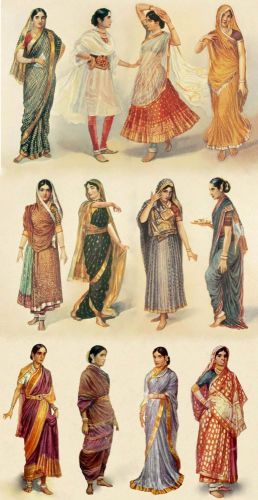

Saree

Women typically wore a saree with a blouse and petticoat.

The traditional Indian women’s wear, saree is a long, rectangular unstitched garment. It is wrapped around the waist, and one end pulled over one shoulder.

Normal dimensions are between 4.1 and 8.2 m (4.5 and 9 yards) length, and between 60 and 120 cm (2 and 4 feet) width.

Some examples of Saree

Watercolor by DUMAS Jean Baptiste Louis, 1827, with the courtesy of IHOI

Regional name variations

Down south, blouses are named kuppasa or ravike. North Indians call it choli while the Nepalese term is cholo. The petticoat is variously termed parkar, ghagra, and ul-pavadai.

Gharara

Gharara originated in the Lucknow region of Upper Provinces (present-day Uttar Pradesh).

A trouser with broad legs that hang out wide from the knees, the gharara is worn with a thigh-length kurti (tunic) and a dupatta or veil covering the head. Odhani/orhani is another rectangular, unstitched cloth that covers the upper torso and is worn over a kurti.

It can also cover the head and face like the dupatta.

Nostalgia & pragmatism : the driver of cultural synthesis

Coming back to cultural blending, migrants try to create the original milieu, the homeland they left in search of a better life. After all, human beings are creatures more of emotion, less of logic. It is this quest that makes them cling to their old ways. Pragmatism, however, dictates adjustment to the realities of the new land.

Through this evolves a hybrid culture, similar to the original but also influenced by “other” people’s lifestyle in their adopted land. As early as the first half of the 19th century, for example, Indian workers on Reunion were burying their dead, not cremating as earlier.

East Indian Indentured Labour Celebrating on a Trinidad & Tobago Estate. Credits: Project Gutenberg at Wikipedia

Maintaining the caste structure in new lands was tough business. Women from the same caste were not always available for marriage. And, having to share living quarters and food without knowing their caste (they came from different parts of India), demolished many social barriers.

Workers did try to cling to old identities though. For example, when they discovered that an immigrant in Trinidad was a Brahmin, they did his manual work and asked him to undertake religious activities instead. Old habits die hard!

But because culture influences identity, it usually forms the foundation of many a conflict. Identity politics, for example!

Hosty massacre (1884) : culture, identity, politics & conflict

Colonial authorities ordered gun firing on the participants of the Hosay Procession on 30 October, 1884 in San Fernando, Trinidad. The procession violated prohibitory orders issued earlier. Although based on the Islamic Muharram festival, the Hosay Carnival evolved into a multi-religious, Indian festival in Trinidad.

While the carnival reminded them of Indian village life, indentured workers also used it as an instrument to strike against plantation owners and demonstrate religious unity in Trinidad. Of the 100-plus killed in the massacre, most were Hindus.