Reenactment of the Cafrine's costume

Part 1: Research

A cafrine & her baby

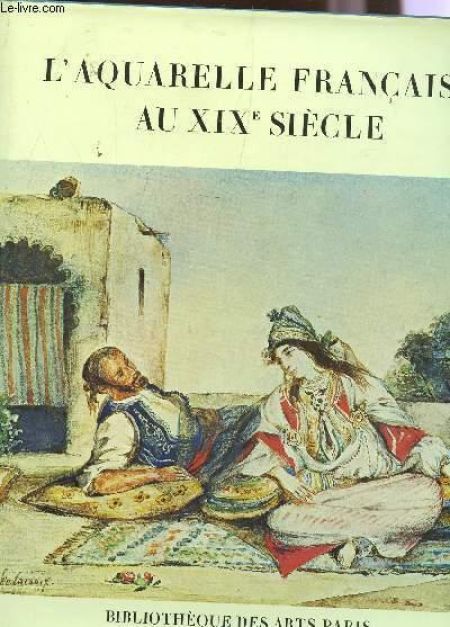

We are proud to present our latest historical re-enactment project, based on this watercolour of Charles Hippolyte Napoléon Mortier de Trévise, dating from 1861.

To make sure you don't miss out on any information, here is an article about this character, Hippolyte Charles Napoléon Mortier of Trevise, who was a close associate of the court of Napoléon III.

A triptych of articles will be published about this cafrine, including

- research, by our researcher Dominique VANDANJON-HERAULT

- the making, by our project coordinator Alicia PIOT BOUYSSE

- the results, by our entire team

Watercolour by Charles H. N. Mortier, Marquis de Trévise: Au Tampon, Une cafrine et son petit, 1861. Held at the Archives départementales de La Réunion, 40 Fi 76. Dimensions: 18 cm x 13 cm

The elements of this watercolour

This watercolour was painted a dozen years after the French abolition of slavery in 1848. The title, which is not visible here, was given by the artist.

It shows a young mother, barefoot, dressed in a loose blue dress made of Guinea cloth, carrying her baby on her back with the help of a colourful loincloth. A red scarf is tied on her head, looking almost like a Phrygian cap. Her baby is protected from the sun by a handkerchief placed on her head.

There are a number of compelling elements in this illustration:

This young woman is not named, which is unusual, it seems, for Mortier de Trévise, because in the album he produced during his two voyages to Réunion Island, in 1861 and 1866, he took great care to name most of the people he met, even fleetingly, at random ports of call, in Malta or Egypt for example.

"Cafrine" means that she is not Creole, so she was not born on the island. On the other hand, the term Cafrine already had, at that time, the sometimes affectionate meaning that survives today. In this case, this woman could be the daughter of a Cafrine who arrived from the east coast of Africa during the period of slavery.

Jean-Baptiste DUMAS, Watercolour extract, Archives départementales de La Réunion. This other, older watercolour dates from the previous period, that of slavery. What is most interesting is that the young woman sketched by Jean-Baptiste DUMAS in 1830 is wearing virtually the same type of dress as our Cafrine, almost thirty years later! What kind of fashion could there be for workers who didn't own much? The cut of the dress is very similar, and the fullness of the model means that a woman can wear it even during the months of pregnancy...

Here again, something unusual about our watercolourist: he scrupulously followed the recommendations made in the most reputed works on the new art of watercolour painting at the time - for example, Constant VIGUIER and Langlois DE LONGUEVILLE's book, republished several times since 1827 - which recommended starting from the vanishing point and drawing the figures slightly low in order to render them as truthfully as possible.

But here, it raises questions, because the artist had to kneel down, even slightly, to capture the young woman's pose - a strange attitude, wouldn't you say, for a marquis, in front of a woman of very modest means, or even a freedwoman?

As the child's head is bent over, you might think that he is only a few months old, barely four. But trying to recreate the garment with a slightly older child produced the same visual effect, when the child, tired from the shooting, fell asleep!

The presumed age of the child suggests a birth between the second half of 1860 and the beginning of 1861: this enabled us to search for potential candidates for this 'cafrine', by delving into the Saint-Pierre civil registers for that period.

In 1860, there were 553 births, and 666 the following year, for an unknown number of inhabitants in the commune at that date. We know that the total population of the island was around 200,000, of which Saint-Denis accounted for almost 36,000. In any case, there were far more births than marriages, and a very high infant mortality rate, affecting both the wealthy classes and the poor.

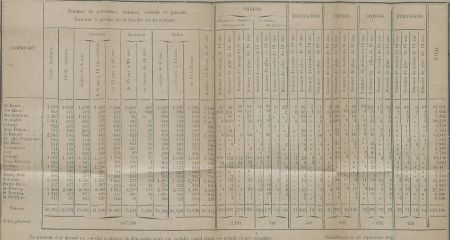

As for the difference of around a hundred additional births in 1861, this testifies to the vigour of the immigration of workers, more or less forced, who arrived on the island after 1848. This is known as "engagisme". This is what appears in this statistical document extracted from the Archives départementales de La Réunion for 1921, a year in which "engagisme" continued, and therefore the counting of the population according to geographical origin.

It may be that this young woman holds either the key to the Château de Bel Air, the air-changing residence of the masters of the estate, the Kerveguens, or the key to the infirmary.

If we look at the births that took place in Le Tampon, we find few candidates who were both young and worthy of the trust of the masters to take on such a responsibility at such a young age.

This was the case of Marie Axida ARTICHAU, aged 17 in 1861, who had given birth to a boy named Jérôme on 5 September the previous year. The father, aged 27, was Désiré APOLLODORE, a servant at Kerveguen, in Le Tampon.

Another candidate was Clémence ROBINET, a 27-year-old servant, married to Edmond SALBRIS, a 34-year-old domestic servant. In August 1860, little Gabriel was born to them on rue de la Plaine, where they lived. The witnesses for the birth certificate were freedmen, former slaves of Gabriel de Kerveguen. Gabriel de Kerveguen had just died accidentally in March 1860 in Paris, where he had gone on business to prepare for the marriage of his daughter, Emma.

Did the young parents, Clémence and Edmond, wish to honour the memory of the deceased by naming their child Gabriel? It can only be as a sign of recognition of a possible generosity: a piece of land, given to cultivate in colonage? - A method of farming in which the land remains the property of the master, but the fruits are shared between the farmer-settlers and the owner...

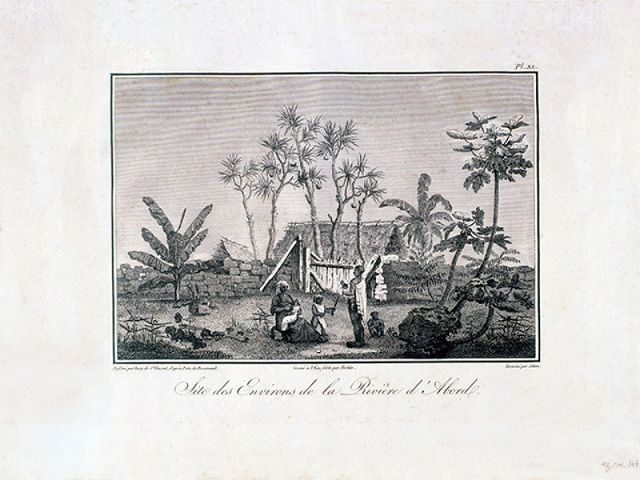

An example of a living environment

Site around Rivière d'Abord, lithograph by Jean-Joseph PATU DE ROSEMOND. Preserved in the Musée historique de Villèle, La Réunion.

This drawing gives an idealised image of the Creole family, or the families of workers, even slave workers. In particular, it gives the impression of a fairly easy life, with no shortage of food in the form of fruit trees: banana trees, papaya trees, breadfruit trees, vacoas, the fruit of which can be eaten, while the leaves are used to make mats and packaging bags...

Deliveries

"Negresses are good mothers and, whatever has been said, they do not use any abortifacients. And what interest would they have in having an abortion? A population of twelve or fifteen thousand souls has not given us the opportunity to observe any abortion that could be linked to criminal means. Their good conformation, the great development of their pelvis, the dilatation and softness of the fleshy parts, all combine to make it easy for these slaves to give birth, which is almost always presided over by an old birth attendant".

This extract from the text reflects the author's prejudices, but it also bears witness to his experience in the field. The 12,000 or 15,000 souls he refers to are undoubtedly those of the sector of the island that was assigned to him.

Who are these 'birth attendants'?

The birth attendants were matrons, an occasional profession that had existed almost since the island was first colonised.

Before 1848, they were experienced slaves, who even delivered white mistresses, which is not unequivocal as to their status.

It was these matrons who registered births out of wedlock. We know the names of a few, in Saint-Pierre for example: Gerville Célestine, née Victoire Coralie, who was 56 in 1861.

They also explained how to prepare herbal teas to be taken before and after childbirth, such as infusions of ginger or green saffron.

They also gave advice on caring for newborn babies, with herbal teas to be administered to help them evacuate the meconium from their intestines, or to combat tambav - the Malagasy word for infant colic...

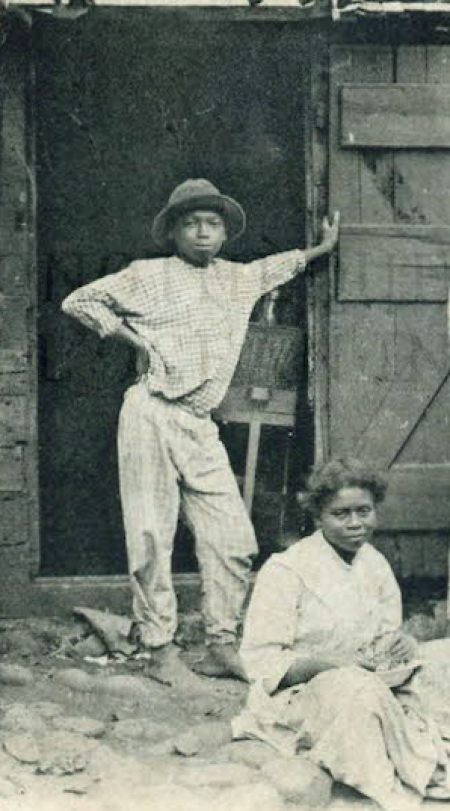

Ma-Marie, Sage-femme, photograph in the Musée des Arts décoratifs de l'océan Indien, MADOI, inventory reference: 18P1.7_PHO.2012.2274.35a

"The descriptions given by the matrons attest to both prenatal care (palpation, examination, touching, administration of herbal teas, pro-phylactic advice) and postnatal care (post-natal care, healing baths, care of the newborn), as well as a high degree of availability and professionalism. In addition, the accounts of the births reveal knowledge of various obstetric techniques that were particularly difficult to apply. These techniques were not used "on the spur of the moment" but in specific contexts and following a long apprenticeship."

This extract is taken from a contemporary description, in the twentieth century, but it could very well apply to the matrons of the previous century: they too possessed a know-how based on experience, and great attention to young mothers and their children. They knew how to turn a baby inside out if it was not upside down, or how to detect twins. That said, they are the first culprits exposed to public vindictiveness if accidents occur. They are therefore very cautious, even though infant and perinatal mortality rates for young mothers remain very high, due to a lack of hygiene and the many recurring epidemics.

Mortality and health care in the 19th century

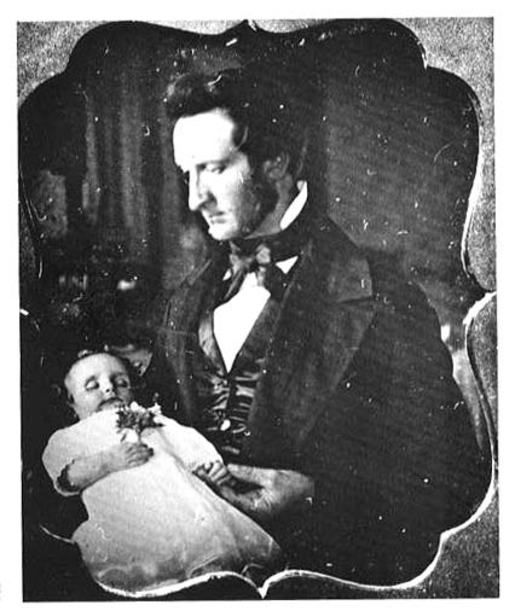

Infant mortality

It affected all social groups, from well-to-do families to the poorest workers.

A fashionable practice at the time, with the beginnings of photography, was for wealthy families to take photos of themselves with the deceased. See the work on the "mourning portrait" and its role in mourning.

It is likely that the Belgian photographer EYCKERMANS (whom we will talk about soon) was involved in this practice on Reunion Island.

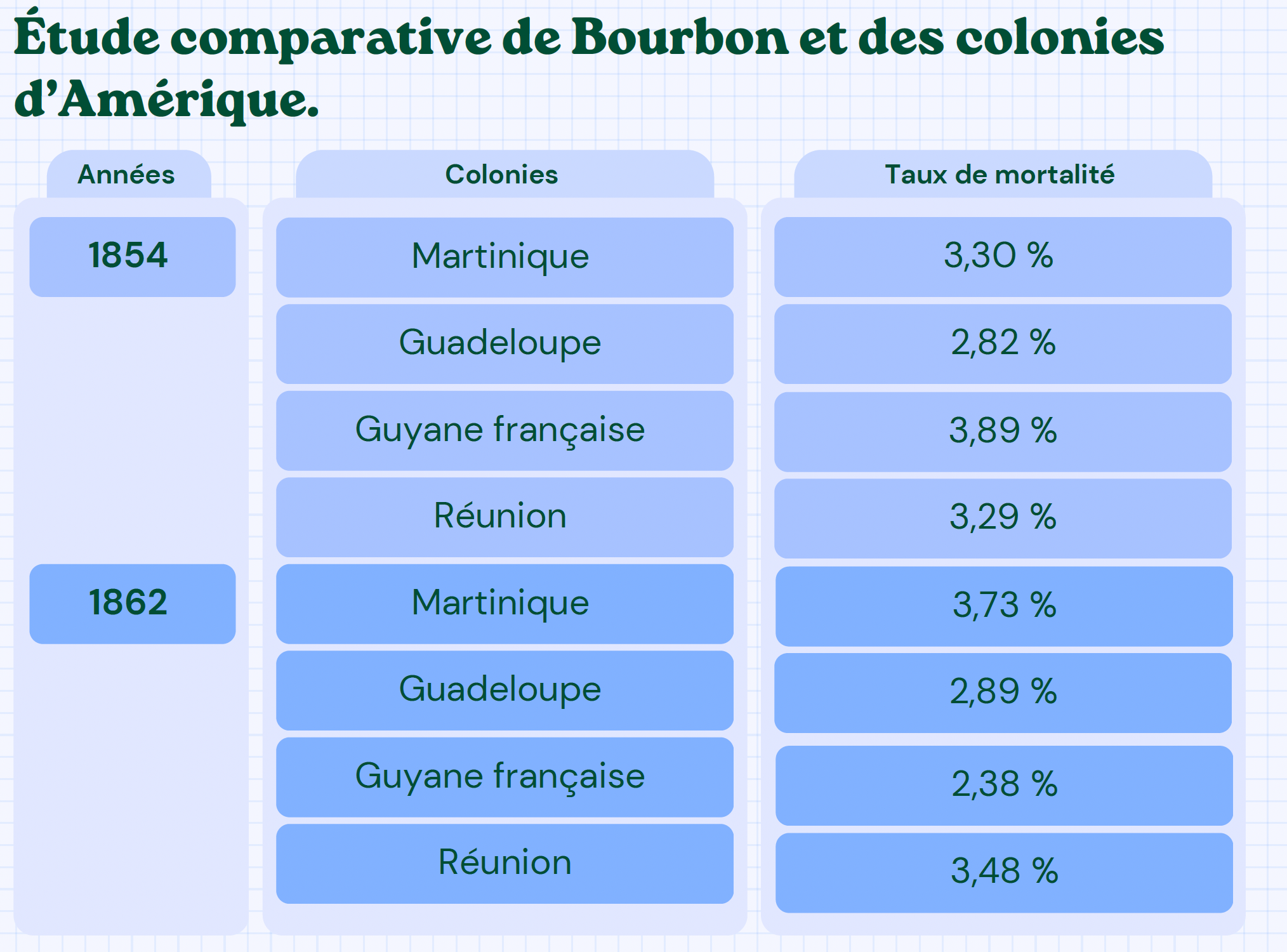

General mortality

The main cause of death, linked to the recruitment of Indian workers (until 1882) and then Africans, Madagascans and Comorians, was malaria. Or cholera. These diseases did not really disappear until the middle of the twentieth century.

Table produced by Pauline TAMARA, student, based on data from the economist HO Haï Quang

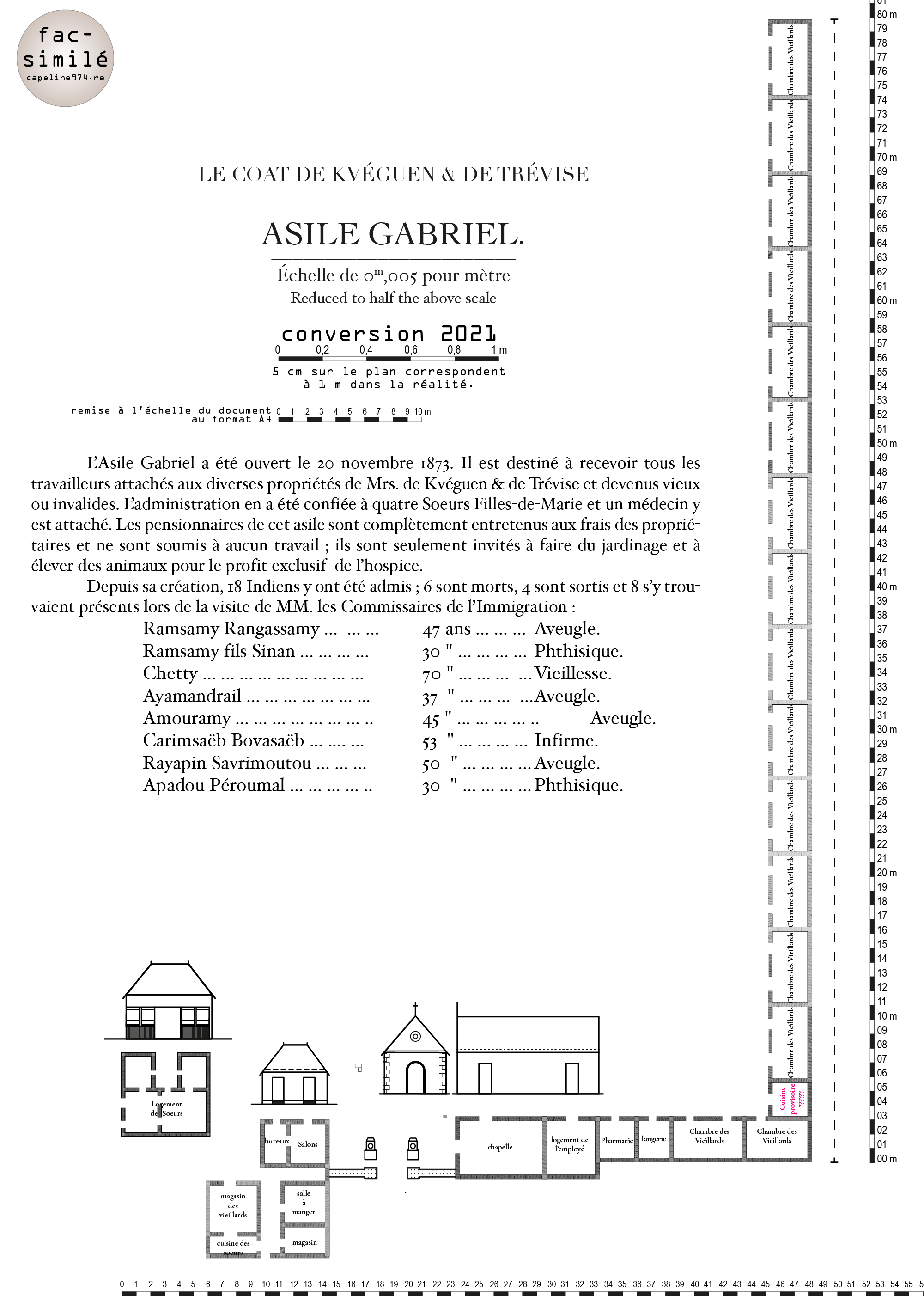

The hospital's key

It was compulsory for owners of factories and large estates to build a permanent hospital, especially after the cholera epidemic of 1859.

The key around the young woman's neck may be that of the Bel Air hospital, of which nothing remains. Medicines, food and a change of clothes were stored there, and sometimes the hospital was even used as a remand centre for minor offences. Hence the need to lock the building.

The facsimile below shows the plan of an asylum for the infirm and elderly, built by the Kerveguen family in a somewhat isolated location near Saint-Pierre.

In any case, it was not customary in those days to give birth in hospital, except in cases of force majeure.

The suite of this triptych is coming soon!

In the meantime, you can follow our research and discoveries on social networks, and get in touch with us.

You can also find out more on the belair.hypotheses.org website (in French), where research other than that linked to the Forget me not project, but not so far away as all that, can be found...take a look, you'll learn a lot :)