Sewing machines in the 19th century

After our articles on

- Sewing machines in the 19th century - Part 1: a brief history

- The sewing machine in the XIXth century - 2nd part : Arrival on the Réunion island

This is the last article of this triptych, which we hope will allow you to better imagine and understand the historical context as well as the practices related to the making of clothes at the time.

While doing research, I was surprised by certain points which were not without making us think of recent events. I let you discover :)

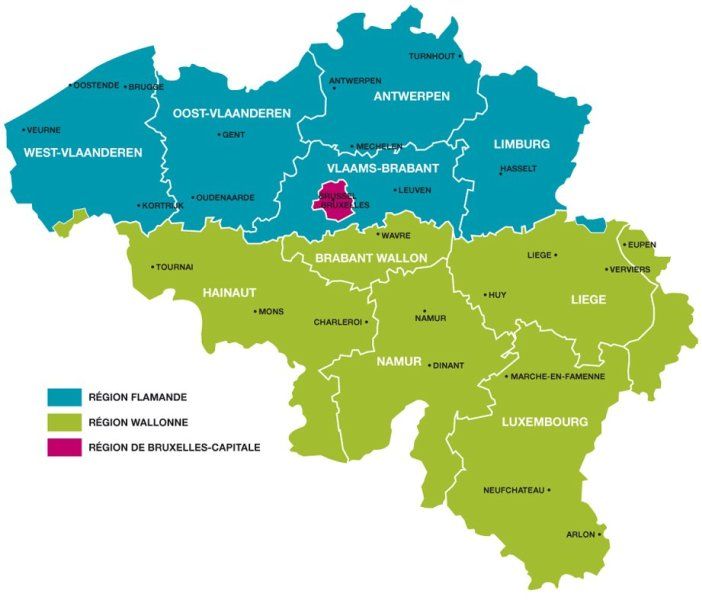

Geography of Belgium

Although I am sure that our enlightened readers know Belgium very well, I would just like to make a small summary of the topography of the territories while adding some quick information about the different major industries present in the 19th century

Gand

Cotton and linen industry

Wetteren

Cotton industry

Termonde

Cotton industry

Renaix

Cotton industry

Saint-Nicolas

Cotton industry

Courtrai Izegem

Linen industry

Verviers

wool industry

Ensival

wool industry

région du Borinage

coal industry

la Louvière

coal industry

Région de la Basse Sambre

coal industry

Pays de Liège

coal industry

Still specialised in the textile industry today, this region has become richer since the end of the Second World War thanks to the benefits of its port infrastructure.

For our Anglophone readers, you should know that the Flemish speak... Flemish, a dialect of Dutch.

If you feel like it, you can click on the little Dutch flag at the top of the page to discover our articles translated into this language. Belgium being trilingual, we have chosen to translate everything into Dutch in addition to English and French.

The Brussels region, enclosed in Flanders, includes the city of Brussels, the capital of Belgium and of Europe.

The official languages are French and Flemish.

The textile industry in this area will be developed further in the article.

Very rich before the Second World War thanks to territories allowing the excavation of materials such as coal.

The Walloons speak...Walloon, dialects of French.

There is a significant presence of the cotton, linen, wool and coal industries.

The Belgian textile industry

Most industrial revolutions take place in attractive centres, and Brussels is no exception to this rule. That is why I propose that we focus on this capital.

Postcard from the Brussels World Fair, 1897

How did people get clothes before the arrival of the sewing machine?

It is not always easy to imagine a society where ready-to-wear clothing was not yet the norm as it is today. The first "Grand magasin" - Au Bon Marché - appeared in Paris in 1852, and it would take a few decades before the industry and commercial networks made it an almost globalized generalization. Our period of study is thus situated at this pivotal moment when sewing is still a common necessity for most people, and a vital skill for some.

"Before the 1830s, anyone who wanted to buy a garment had several options, depending on their financial means.

The middle and upper classes turned to qualified tailors and seamstresses who made the requested article to measure.

Those who could not afford it could buy their clothes on the highly differentiated second-hand market or make them themselves."

les Cahiers de la Fonderie, n°15, december 1993, “le vêtement et les dessous de la confection” d’Eliane GUBIN and Jean PUISSANT

Tailor

A person, craftsman who makes custom-made clothes; a person who runs the workshop where they are made. "To have a suit made to measure at a tailor's."

Does the expression "sitting in a tailor's shop" come from this profession, where the tailor, sitting on the table, works with his legs crossed, like the one on the top right of the picture ? ...but I digress...

WENTZEL Jean Frédéric "Der Schneider" (the tailor) 1847

Source Gallica BNF

Tailors and the sewing machine

The target audience of our project (working class) probably could not afford to pay for a tailor for their outfits. However, I would like to show the evolution of this trade following the advent of sewing machines, as the changes were visible outside the tailor's trade alone: the whole fashion industry was profoundly changed.

"The only major technological innovation for tailors is modest in appearance: the sewing machine. Although it was introduced in Belgium around 1860, no figures are available on its spread. Despite initial resistance, it seems to have spread rapidly to the point that by 1900 the majority of tailors were using them." (les Cahiers de la Fonderie, n°15, december 1993, “les tailleurs Bruxellois au 19ème siècle” de Sven STEFFENS)

- Sven STEFFENS mentions "resistance", but what is it?

In the article Sewing machines in the 19th century - Part 1: a brief history, it was mentioned that the creation of Barthélemy THIMONNIER's machine had provoked strong reactions, particularly among tailors, who in protest had burnt down his workshop.

Source Gallica BNF

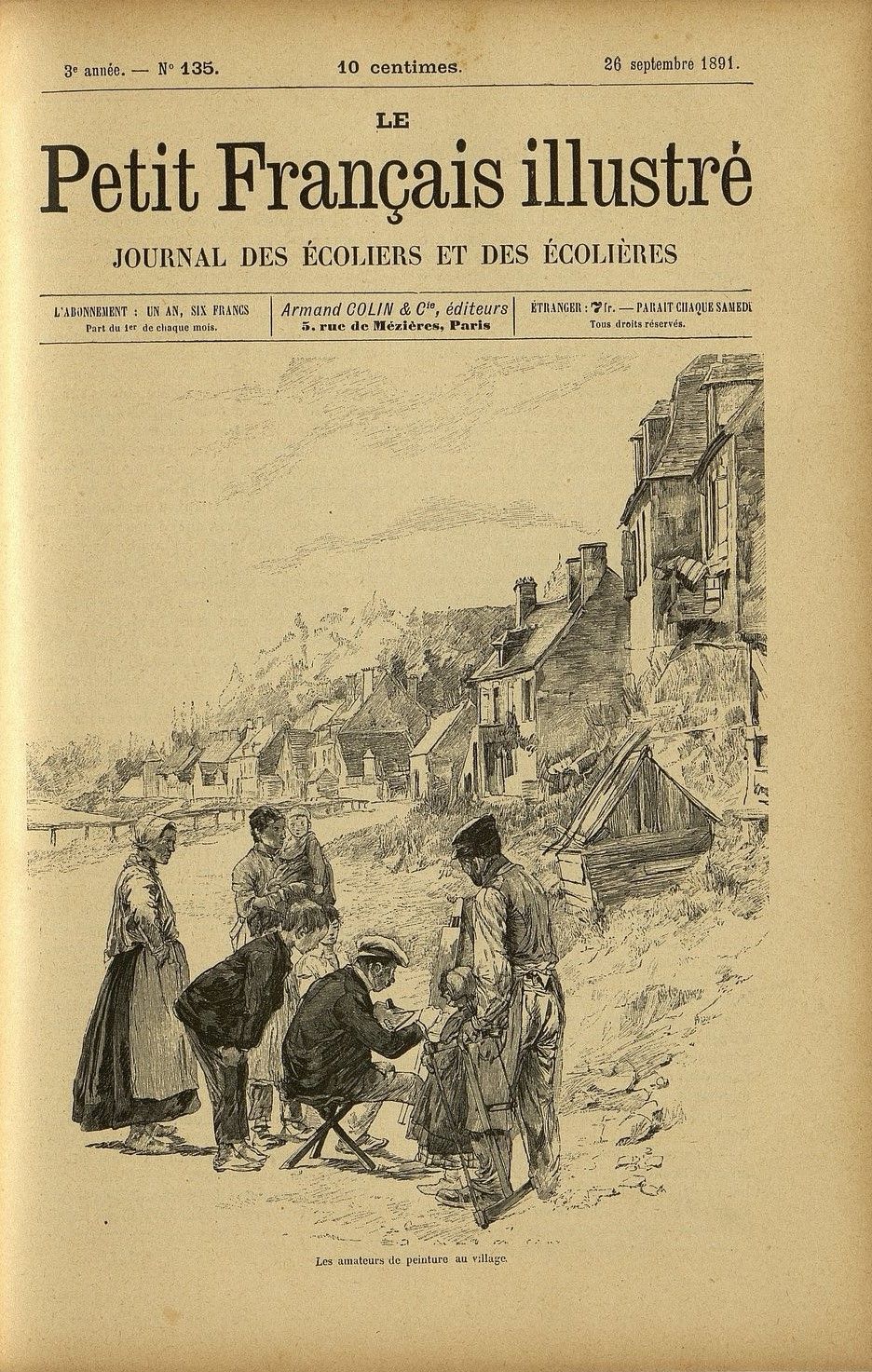

Opposite "Le petit Français Illustré" of 26 September 1891, an example of a publication in which the history of Barthelemy Thimmonier's invention is discussed: the hostility encountered when his machine was launched is mentioned, as well as the efforts made to have his machine and that of Elias Howe (an American sewing machine designer) accepted

The manual workforce of the industry in the 19th century

Although not all tailors adopted the sewing machine in their shops and/or workshops, others saw an interest in it: entrepreneurs.

A pyramid system was set up with

- entrepreneurs (who take care of buying raw materials and canvassing customers)

- intermediaries (looking for subcontractors to meet customer demand)

- workers (sometimes working in workshops, more often from their homes, thus taking charge of costs other than raw materials, i.e. the purchase of the machine, its repairs, and costs arising from working at home, which we know now that we have all recently experienced a confinement...)

"This market was increasingly offering cheaper and cheaper products, as they were saving on labour, as clothing entrepreneurs were increasingly resorting to subcontracting and especially to a particular form of subcontracting: home working."

Léon Delachaux, La Lingère - Intérieur, Circa 1905, ©Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

"Why did these entrepreneurs opt for a decentralised production system in the factory age, when from 1840 onwards a huge technical advance had been made with the invention and further development of the sewing machine? The arguments put forward for the choice of decentralised production in the 19th century clothing industry are those that had been valid for some centuries for the "putting-out" system: the commercial entrepreneurs in question could limit themselves to placing the order and dealing with the purchase of raw materials and the sale of the finished products; all the burdens and costs associated with production fell to the subcontractors."

[...]

"The capriciousness and unpredictability of demand were not conducive to investment in buildings and machinery that were likely to remain unoccupied or under-occupied for a certain period of the year. [...] The scarcity and high cost of land and buildings in the centres (Western European capitals and large cities) was a further argument against concentrating production."

(les Cahiers de la Fonderie, n°15, december 1993, “le prix de la confection” de Patricia VAN DEN EEKCHOUT)

In "les cahiers de la Fonderie" n°15 of December 1993, Patricia VAN DEN EEKCHOUT and other authors (quoted above and below) explain very well the transformations of this industry. I recommend reading this document (digital format, for a fee) if you wish to learn more and see the transformations up to the 20th century.

To do this, contact the documentation centre of the Brussels Foundry Museum, they are very attentive and responsive. Also visit the museum if you have the opportunity ;) It is worth a visit.

Mass retail

Between the consumers and the producers, wholesalers and retailers gradually set up, which from the middle of the 19th century onwards would become :

department stores.

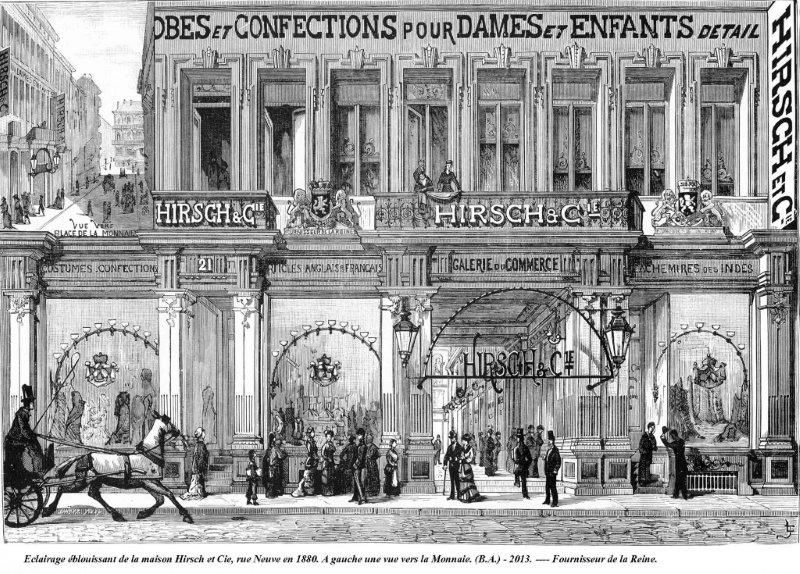

In 1869, the famous Hirsch et Cie shop opened on the Rue Neuve in Brussels, a real "ladies' delight" as Zola called it. This shop, well known to the people of Brussels, specialised in luxury women's clothing and attracted a wealthy clientele.

For more information on Hirsch Stores, I recommend reading "Hirsch & Cie" by Véronique POUILLARD, available for free on the Academie.edu website

Another change that has followed the acceleration of this industry is worth noting:

The newspapers of the time show a rapid evolution of styles (for the time) and incite the bourgeoisie to change in order to remain "à la mode".

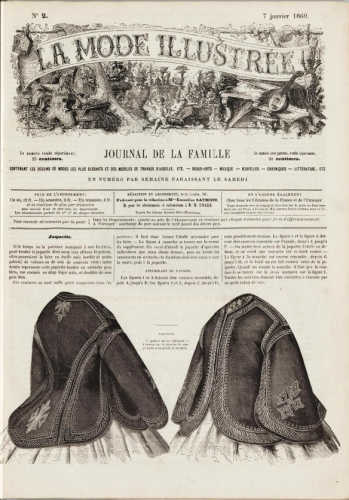

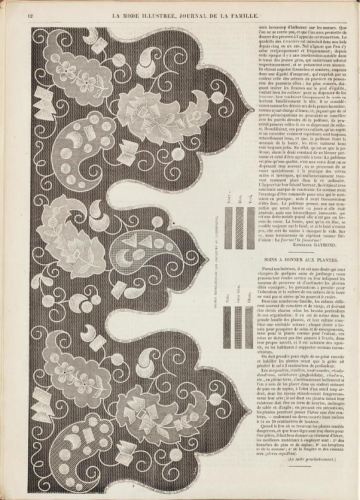

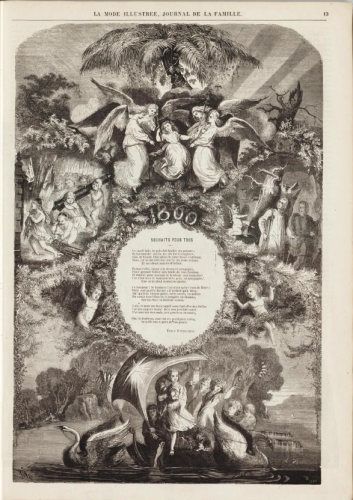

An example of a newspaper: the weekly La Mode Illustrée, created in 1860, whose issue of 7 January 1860 is available on the website of the Library of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris

You can see that they not only introduce styles, but also give instructions for crafts, stories, readers' mail, etc.

The scale of the phenomenon

"Compared to the country, employment in the Brussels garment industry exceeded 20% between 1896 and 1947".

[...]

"In 1896, the clothing industry was the most important sector both in terms of employment (salaried and self-employed) and the number of establishments. There are as many workers in the district of Brussels as in all the others combined."

(les Cahiers de la Fonderie, n°15, december 1993, “une capitale de la confection” de Michel DE BEULE)

"District" of Brussels

In Brussels Capital, there are 19 communes, including the commune of Brussels

A sector almost as flourishing as coal

"Thus, according to the industrial census of 1896, the garment industry employed approximately 107,000 people in Belgium (employers, employees and workers combined) and was second only slightly behind the coal industry with approximately 122,000 people and well ahead of the building industry with approximately 67,000 people. Moreover, in Brussels, the clothing industry is clearly in first place: the 1910 industrial census shows 11,980 people for Brussels city, the second largest sector being the building industry with 4,303 people."

La Maison du Peuple of Brussels

Famous building, meeting place in the city centre for the Belgian Workers' Party. Others have also existed in other cities

Working from home is the norm

[...]

"A particularly revealing detail of the importance of homeworking is provided by the experience of the socialist clothing cooperative in Ghent: in the 1880s, the Vooruit Gantois tried to keep its workers in the workshop in order to offer them more humane working conditions. However, from the point of view of productivity and in the face of 'capitalist' competition, the results were so inconclusive that in 1898 the company had to give up this system and resort to working at home. Dissuaded by the Ghent experience, the clothing production cooperative of the Maison du Peuple in Brussels automatically applied home work."

[...]

"The extension of home work must have accelerated considerably in Brussels during the 1860s and 1870s, since in 1880 the Brussels tailor merchants founded a professional school for tailors, the first in the country. As justification, they put forward the suppression of most workshops and the defects encountered in the apprenticeship as practised by home workers".

(les Cahiers de la Fonderie, n°15, december 1993, “les tailleurs Bruxellois au 19ème siècle” de Sven STEFFENS)

The establishment of vocational schools

If the subject leads you to think that I am going astray, let's look together at how this relates to the subject, and the importance it took on from 1860.

"Another element that indirectly signals the rise of home-based work is the debate around the apprenticeship crisis. As workers work at home, apprentices are trained at home and no longer in the workshop of the master cutter. In the absence of guidance from the master tailor, without constant comparison with the skills of other workers previously found in the same workshop, and in view of the decreasing work requirements encountered in the field of tailoring, the professional qualification of the workers suffered a definite deterioration."

(les Cahiers de la Fonderie, n°15, december 1993, “les tailleurs Bruxellois au 19ème siècle” de Sven STEFFENS)

Marianne de VREESE writes in "l'Association pour l'enseignement professionnel des femmes et les débuts de l'école Bischoffsheim à Bruxelles, 1864-1868" (link to the pdf)

"In the 19th century, many women found their livelihood in work. Uneducated, subject to a long apprenticeship in an often unhealthy workshop, at the mercy of a boss who was initially very concerned about profit, working women were victims of all kinds of prejudices and exploitation. From 1840 onwards, various attempts were made to improve this situation. In theory, it was easy to criticise the workshops and denounce the ignorance of women, but providing a real and effective solution discouraged many, while others seemed to accept it."

Institutes were created to train tailors or dressmakers, but unfortunately the female sex was always left out because the Belgian law of 1850 establishing official education had overlooked the education of girls and women teachers: all that remained were religious schools and boarding schools. This lack of perspective certainly explains why their 'poor level', criticised by employers, was not due to a deficient intelligence quotient, but rather to the educational situation of the time.

Around 1860, a feminist movement originating in England spread to the continent and bourgeois society became concerned about the education of future housewives, who were the soul of the home.

Public opinion, mainly liberal and bourgeois, was moved by the misery, especially moral misery, of the working classes. A desire to extend education to all social strata took shape because: "it appears that it is the intellectual inferiority of the worker which is the cause of his social inferiority. [...] Integration is better than segregation if we want to maintain the established order", Marianne DE VREESE continues to explain.

The idea gained ground, and attempts were made to learn the trade, combined with general education, but nothing really lasted, because the apprenticeships were done in the workshop, and the bosses were more concerned with learning the trade and their production, than with learning their employees.

In 1862

Elisa LEMONNIER opens the first vocational school for girls in Paris, run solely by women for young women.

The programme includes general education, common vocational education and specialised courses. These courses are open to girls from the age of twelve.

Elisa LEMONNIER

In 1864

Zoé GATTI DE GAMOND

Zoé and her daughter Isabelle worked hard for the emancipation of women in Belgium, notably advocating equality between men and women in the field of handicrafts because the work produced is of equal value.

She also campaigned for the opening of schools for working class girls, financed by the upper classes.

Her daughter, Isabelle, took up the torch and somewhat overshadowed her mother, but her work is still remarkable, notably with a middle school for girls in 1864 in Brussels.

This site of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation explains the difficulties of access to education for young girls in the 19th century if you wish to know more.

In 1865

Jonathan-Raphaël BISCHOFFSHEIM was a financier, a liberal politician and distinguished himself by his philanthropic actions.

In 1864, the Association for the professional education of women was created, which took the name of one of its main founders, Mr BISCHOFFSHEIM, in 1891.

This school has continued since then with the Bischoffsheim Institute, a vocational secondary school in the field of textiles, art and hairdressing.

Jonathan-Raphaël BISCHOFFSHEIM

The schools promote their teaching as follows

"In order to improve the lot of women, to combat their ignorance and destitution, the sources of all misery and degradation, to offer them better chances in life while giving them more moral strength and more security against the dangers to which they are exposed, the programme of the new school combines general education and vocational courses."

and are a great success!

Professional school Bischoffsheim, Brussels. Drawing course 1st year

What about today?

The tailor's profession

En cherchant des exemples de tailleurs, j'ai effectivement trouvé quelques exemples (principalement masculins), et souvent proches de la retraite, dont voici une toute petite sélection.

The decline in demand did not favour the development of this trade for some decades. But if one can think that they will disappear, I can assure you that this is not the case because recently the techniques have regained a certain prestige.

I would like to share with you some "influencers" specialised in the creation of customised clothing, whether it be historical, artistic or just made-to-measure.

Barbara Pesendorfer

founded Royal Black in 2006 and creates creative pieces with particularly precise tailoring techniques

Zack Pinsent

tailor specialising in the creation of historical costumes, with a focus on ecology

Bernadette Banner

specialising in the reconstruction of late 19th century clothing

and incidentally, his great book

Even if you're new to sewing, I recommend taking a trip to Instagram with the hashtags #bespoketailoring or #tailor to feast your eyes on real tailors at work, with such ease creating beautiful custom pieces...!

In fact, our styling, finance and networking advisor, Line DE MUNNYNCK, works at Café Costume, a tailor-made clothing house run by the famous VAN GILS family, which has been dressing men and women for over 70 years.

See how this practice of wanting a nice suit for events continues :)

Sewing in general

an exemple of article, source fashionrevolution

Funnily enough, now that the COVID pandemic is subsiding, we can better examine the trends and behaviours that developed during the containment(s).

Indeed, cooking, bread making, interior (re)decoration but also crafts were popular. Some friends tried to buy a sewing machine, but without success, as their success was such that stocks were quickly depleted.

Ironically, if in the 19th century sewing at home was a necessity to support oneself, in the 21st century during confinement(s) sewing (like other crafts) was a necessity to overcome the boredom of confinement.

Since then, sewing has come back into fashion: we don't sew with a "granny style" anymore, but it's a cool way to participate in "slow fashion" and "upcycling".

Professional fashion schools

What in France is called a 'professional school' is called a "haute école" (high/tall school) in Belgium. You will agree that the choice of name shows an appreciation for the system; no doubt a legacy of what was set up in the 19th century.

I was surprised by the number of fashion and design schools in Belgium, but especially in Brussels! Especially since, from what I read, many French people come to study there.

La Cambre

Francisco Ferrer

Saint-Luc

College Art & Design

Syntra

La Maison de Couture

If by any chance you wanted to go into fashion, you would have a choice in the Brussels suburbs alone!

And if you prefer smaller towns to the big cities, you can also choose from schools specialising in fashion: this Mode in Belgium article gives you an overview of the various institutions in this field, both in Brussels and nationally.

The textile industry in Brussels

In the 19th century, industrialisation allowed the development of various industries, such as those already in place in Belgium (I mean linen, wool and cotton).

Overall, the Belgian textile industry did well in the 20th century, despite conflicts and crises.

- "It was in the early 1970s that the competition became tougher. Imports from developing countries with low labour costs and from Eastern Bloc countries were particularly noticeable.

- In 1974, the Multifibre Agreements regulated international trade in textiles and regulated imports of textile products from developing countries.

- In 1980, the Belgian authorities intervened to support the industry. The Textile Plan includes a set of specific sectoral aids from which the majority of Belgian textile companies benefit, from 1982 onwards. [...]

- The year 1994 was a pivotal one as it marked the end of the Multifibre Agreements. A gradual lifting of quotas led to the total liberalisation of the market on 1 January 2008."

This information comes from the very complete report: "preliminary study: Sewing, fashion and creation" Deepak ONNOCKX and Anne VANDERSCHUREN (available free of charge in PDF in french) from the Service Francophone des Métiers et des Qualifications (French-speaking service for trades and qualifications), validated by the Chambre des Métiers on 12/06/2020), which I recommend reading if you wish to go further into the subject.

The government therefore mobilised to keep its textile industries alive, to the point where the competition became too tough to continue.

Interestingly, there is a Wallonia-Brussels Industrial Heritage site highlighting the buildings formerly used. This shows the importance of the heritage of the different industries for the Belgian territory.

We would like to visit some of them soon as part of our non-profit organisation Objet Témoin :)

A word from the author : Alicia Piot Bouysse

I hope I have been able to show you the importance of the arrival of the sewing machine in the 19th century, and the important changes it brought about. Please do not hesitate to contact us if you would like to share your family's experience on this subject, or if you have any constructive comments on our articles. Of course, the discussion continues on the project's Contact Us, Facebook and Instagram pages!