On the Indigo Route

...tracking the story of the bewitching blue dye

“Bluest of blue . . .” one that rouses passion, desire, and envy! Is how the website Project Bly describes the indigo colour. These emotions come alive as we travel back in time along the winding indigo route through treacherous trails and stormy seas across continents. But its legacy transcends the consequences of these sentiments to reveal an edge of sustainability, so very essential in this age of ecological emergency - true blue never vanishes!

Blue Trails

A good Income for some 17th century Families

Here is an example of the Indigo's value in India back in the 17th century

-4d62a503.png)

An inspiration for a lucrative British commerce

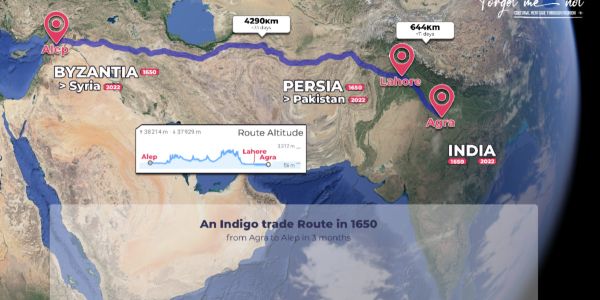

Seventeenth-century English traveller William Finch expected lucrative profits from his twelve indigo-laden carts during Agra to Lahore trips.

Why not? Indian goods fetched thrice their price in Aleppo, Syria. And sea exports to England fetched five times!

But the indigo saga stretches back centuries!

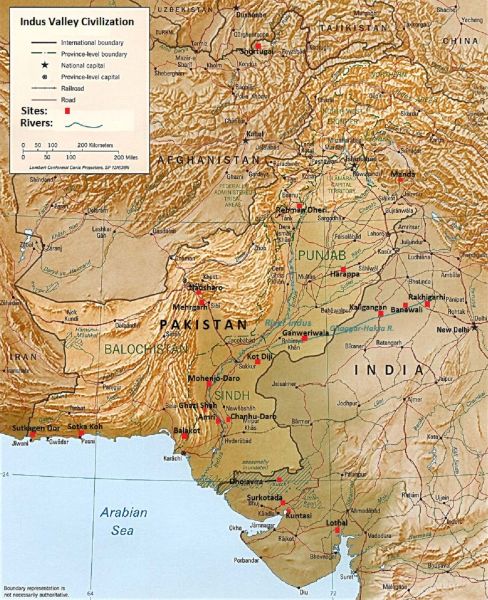

The Indus Valley Civilization

Five-thousand years ago, the Mesopotamias, Cretans, and Persians gobbled the indigo from the fertile fields of the Indus Valley Civilization (present India-Pakistan border).

Etymology

“Indicon” is Greek for “from India.” Perhaps, this enchanting shade first captivated the Greeks and Romans in the bustling markets of Babylon and Assur around the 2nd-3rd centuries. So rare was it, they called it “blue gold!”

Just how far had indigo spread? Here are its names in different cultures:

From Indian continent to almost everywhere

-

A long time ago...in a galaxy not so far away

Indigo domestication, probably near -5000 BC in subtropical regions of Indian Ocean

-

10th-13th centuryIndigo imports via North Africa at it’s peak

To obtain it cheaply, subtropical and tropical import destinations, where it could grow, started farming indigo. Central Asia and Europe now purchased directly from the Middle East farms. This crashed the Indian imports via North Africa. Indigo which, at its peak in the 10th-13th centuries, commanded twice the price of cardamom and pepper.

-

17th centuryRegular Indigo overland & sea trade routes

Land routes took indigo to China and Vietnam from India. Central Asia received it from China. Uzbekistan in Central Asia also obtained it via Persia, from where it moved to Egypt. Overland trade routes of the 17th century include Agra to Lahore and Surat; Lahore to Kabul and Middle East and further; and Sind to Lahore.

Indigo journeyed from India to West Africa by sea. Despite pirates and moody weather, sea routes were safer and used more. Indian centres of overseas trade included Dhaka, Balasore, Chittagong, Hugli, Surat, Ahmedabad, and Bharoach.

-

1865-1880Indigo Dye becomes replicable in Laboratory

Prussian Chemist Adlof Von Baeyer discovers chemichal structure of Indigo, and artificial ways of producing it

-

1897-TodayIndustrialized production of Artifical Indigo spreads, and eventually becomes predominant

for reference, see the Domestication of Plants in the Old World, OXFORD University Press

Did you knew ?

Why do people like it

Indigo catches our eyes because it is the colour with the second largest frequency. Human eyes receive greater energy from higher frequency colours [E]. Once you see it, the temptation “dye” is cast! Love at first sight, perhaps?

Shifts & Conflicts

Despite traveller Sir Thomas Roe describing Indian indigo as England’s “prime commodity” of interest, Indian indigo exports were mainly destined for the Middle East in the 17th. Instead Caribbean indigo kept Europe supplied at this period.

Dutch and British forces allied for it against Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan

But fruitful indigo was! Why would Indian Emperor Shah Jahan monopolize it in 1633? And why would arch rivals British and Dutch join hands to get this revoked in 1635?

Eighteenth century was the heyday for blue-dyed dress coats among the stylishly rich Londoners and Parisians. Unprecedented industrialization in late-18th century Britain spiked textile production, skyrocketing the demand for indigo whose supply from the Caribbean suddenly went dry.

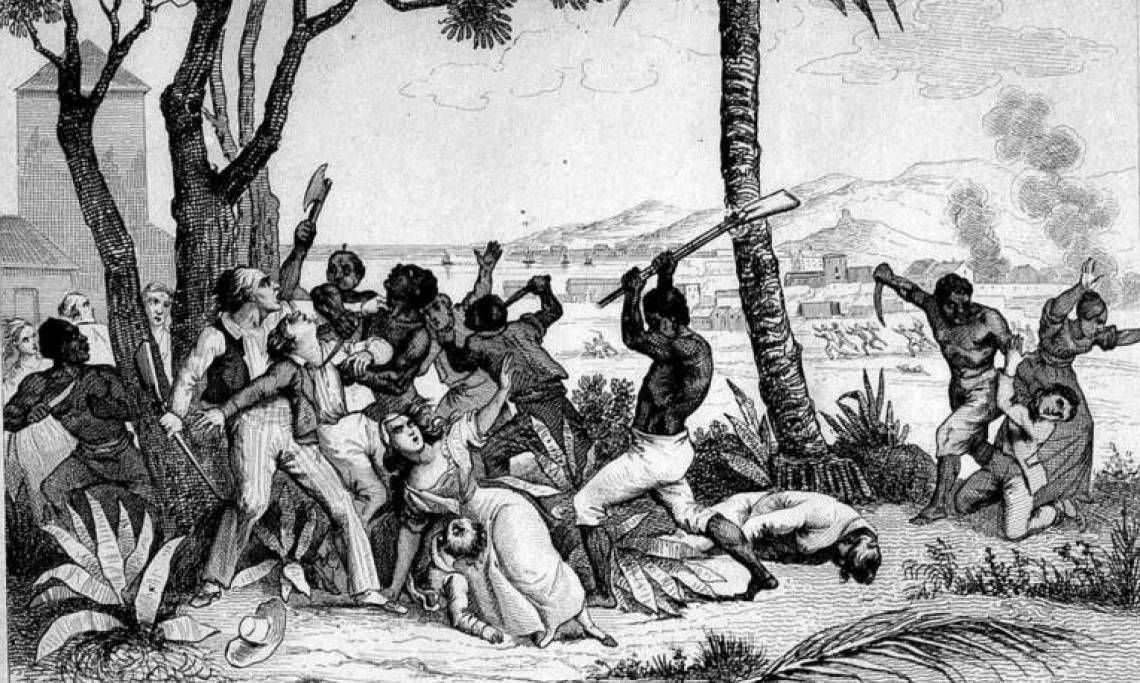

Turn of 19th : the Riots

From Haïtian revolution to french abolition prequels

African slaves rose violently in the 1791 Revolt in St. Dominigue (Haiti), then Europe’s richest colony. Although quelled by 1792, the revolt destroyed the island’s slave-labour-dependent indigo industry as geopolitical compulsions forced France into abolishing slavery in Caribbean colonies in 1794. Freedom eluded French slaves on Reunion Island and Mauritius in Indian Ocean till 1848.

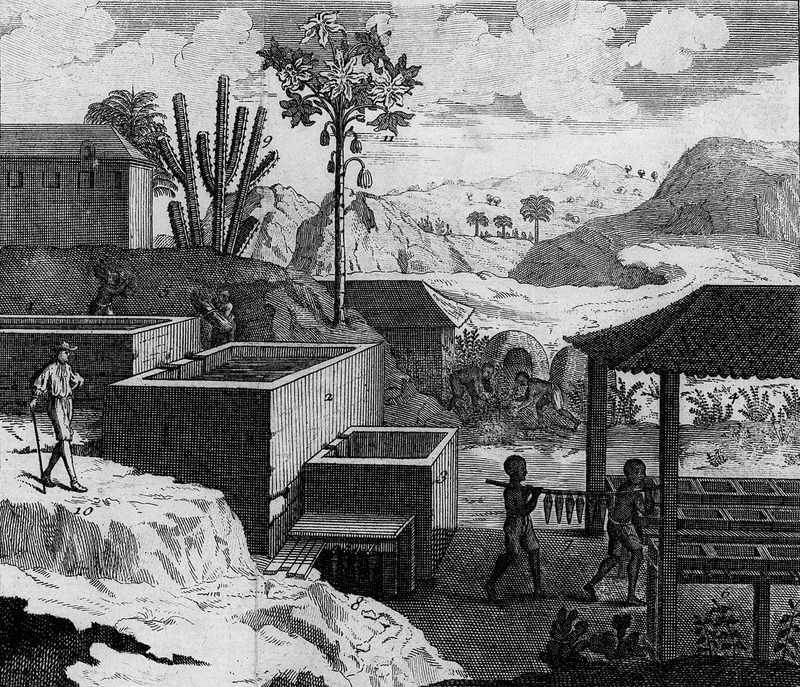

While British almost exploited Bengal for Indigo to nearly the point of starvation

With this, the British expanded indigo farming in Bengal (India). So massive was this shift, India’s share in Britain’s indigo imports jumped from 30% to 95% between 1788 and 1810!

Locals Forced to produce Indigo at unsustainable proportions

|

British planters in Bengal purchased/rented land and hired labour to grow indigo under the nij system, which was profitable only on vast, contiguous land tracts around the indigo factory. Planters needed sufficient ploughs and oxen. Indigo grows in the same season as rice, Bengal’s staple crop. This created paucity of labour, bullocks, and ploughs in the peak season. One bigha (1/3rd acre) of land, for example, required two ploughs. These barriers restricted the nij system to growing only 25% of the indigo. The rest was cultivated under the ryoti system. Planters provided loans, drills, and seeds to the ryots (peasants) under contract and asked (forced) them to grow indigo on 25% of their land, but purchasing only at 2.5% of the market price. Besides, indigo is a “heavy” crop that rapidly saps soil fertility leaving it incapable of immediate rice farming. |

People trapped in debt cycle started to fight back

English planters purchased indigo at throwaway prices, entrapping farmers in a neverending debt cycle. Some evicted farmers to obtain contiguous land tracts. Simmering tensions exploded in the 1859 Bengal Blue Rebellion. Anxious to avoid disturbances in the wake of the 1857 Uprising, British authorities acted fast and blamed it on the planters who shifted westwards to Bihar.

In fine : A Global market based on the reliability of the Dutch suppliers, and reluctance of Europeans to endanger their alliances with Indian rulers

Other Europeans lusting for Indian indigo were Dutch, French, and Portuguese. West European indigo consumption depended on price and legal factors. Often, the Dutch compensated lower English procurement.

Europeans rarely used their superior naval prowess to remove trade barriers that Indian merchants, bankers, or agents sometimes created on land. They preferred petitioning the rulers. Being interdependent, both avoided a showdown that would disrupt lucrative commerce and invite the rulers’ wrath.

Impact & Legacy

Like other imports, indigo altered the entrenched production and exchange practices, consumer cultures, and artistic production methods of the importing Europeans, while eliciting varied responses from governments.

Plantations became theatres of exploitation and uprisings. Only cash crop growers could afford exorbitant land taxes. Famine, artificial food shortages, food inflation, and malnutrition followed forceful cash crop farming on best lands.

However, this trade created awareness of the 17th century global indigo market. Earlier produce was locally consumed. The concern for sustainability could revive natural indigo farming in near future as the effects of cheap but unsustainable synthetic indigo, used overwhelmingly at present, become painfully apparent.

For, there are still those who make it the old way!