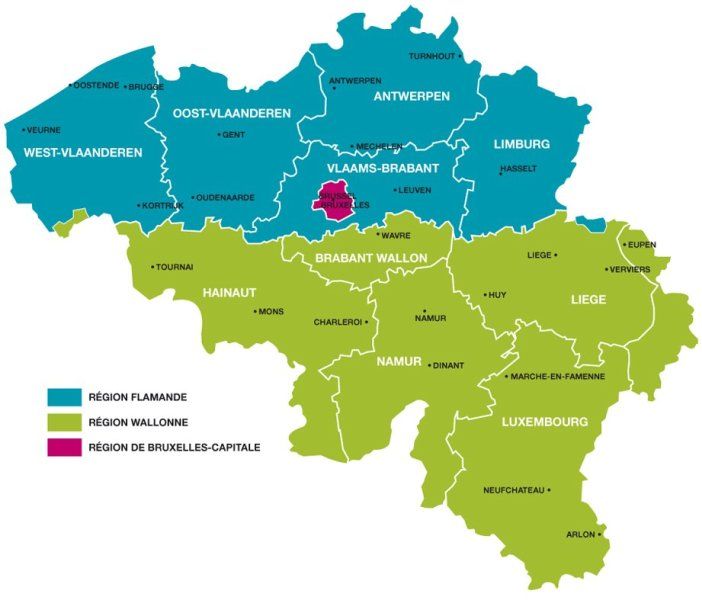

Geography of Belgium

Although I am sure that our enlightened readers know Belgium very well, I would just like to make a small summary of the topography of the territories while adding some quick information about the different major industries present in the 19th century

Gand

Cotton and linen industry

Wetteren

Cotton industry

Termonde

Cotton industry

Renaix

Cotton industry

Saint-Nicolas

Cotton industry

Courtrai Izegem

Linen industry

Verviers

wool industry

Ensival

wool industry

région du Borinage

coal industry

la Louvière

coal industry

Région de la Basse Sambre

coal industry

Pays de Liège

coal industry

Still specialised in the textile industry today, this region has become richer since the end of the Second World War thanks to the benefits of its port infrastructure.

For our Anglophone readers, you should know that the Flemish speak... Flemish, a dialect of Dutch.

If you feel like it, you can click on the little Dutch flag at the top of the page to discover our articles translated into this language. Belgium being trilingual, we have chosen to translate everything into Dutch in addition to English and French.

The Brussels region, enclosed in Flanders, includes the city of Brussels, the capital of Belgium and of Europe.

The official languages are French and Flemish.

The textile industry in this area will be developed further in the article.

Very rich before the Second World War thanks to territories allowing the excavation of materials such as coal.

The Walloons speak...Walloon, dialects of French.

There is a significant presence of the cotton, linen, wool and coal industries.